…and it is all so unnecessary.

Yes, it is true that over the last seventeen thousand years or so, the world has seen annual global average temperatures rise by 5 to 6 degrees Celsius. That temperature rise ranging from about the coldest average temperatures Earth has ever seen (at least in the most recent half-billion years), to something which can only be described as ‘mildly warm’ in comparison to what the planet has endured in its long-ish history. That is inarguable – unless you want to question the records of science which, apart from the last century or two, have been mostly gathered by indirect means. But such doubt is unnecessary. We can trust the science. At least we can trust the record gathering and keeping of scientific data – having no other source on which to base any opposing claim.

But all this has happened before. Most recently just one hundred and twenty thousand or so years ago. And on similar time-scales, many times before that. So what we are witnessing is nothing new. And, in fact, nothing to get excited about. Or to be worried about. And, the current rise in that particular temperature measure ending round about now, or yesterday, last week or perhaps a month or so ago, or next month or next year, it is undoubtedly going to happen. What I am trying to say is that the timing is not precise, in scales which would be of interest to us. [And as evidence this slide to colder conditions may be beginning to happen right now, I will show how that can be tentatively seen in current climate conditions data, further below.]

In the meantime, when that moment arrived or shortly after it does arrive, temperatures will gradually, very gradually, much more gradually than they rose, fall back to the coldest the Earth has ever been, again. That basement level of cold has never been breeched in the past, but as we approach it, within this short term heating/cooling cycle, while, and at the same time as the much longer term planetary cooling trend also seeks to bottom out at the same level (approximately 10 degrees Celsius), the results are basically at this stage, unknown (at least to the best of my knowledge). There is no detectable reason to doubt that as being fact.

Incidentally, we are still technically – which really means ‘really’ – in an ice-age which began some 40 million years or so ago, and has never officially ended. That ice-age, which doesn’t to my knowledge have a name – and there have been a number of named pseudo ice-ages in between (which have come and gone), will continue to persist for millions of years to come. In fact it will not end until the Southern Polar Ice-cap melts (which formed at the onset of the current ice-age) – and that is not likely to happen until a much larger temperature rise (based on long term global averages, not the annual global averages which the average climate scientist so closely favours) to reach higher temperatures than those at which it formed. And that could be tens or even hundreds of millions of years in the future. The last great Ice-Age, during which polar ice-caps formed and eventually disappeared, lasted around two hundred million years (some 360-260 million years before our time). These kind of events are generally considered to result from some kind of ‘cosmic’ interaction with our planet, and often equate with a ‘mass-extinction’ event occurring around the same time. It would be foolish for us to believe that such events will not occur in our future, just as much as they did in our past.

Anyway, as promised, is there any indication that we are at a turning point in the current approximately 120,000 year cycle of ups and downs in global temperatures? I say yes, tentatively, beginning with the current decade. It could, and I would say, must occur at some stage within the next hundred years or so, based on the current temperature rise, which is still about one degree Celsius less than highest two peaks of the previous similar cycles – the ones we know as the Eemian and Holsteinian periods.

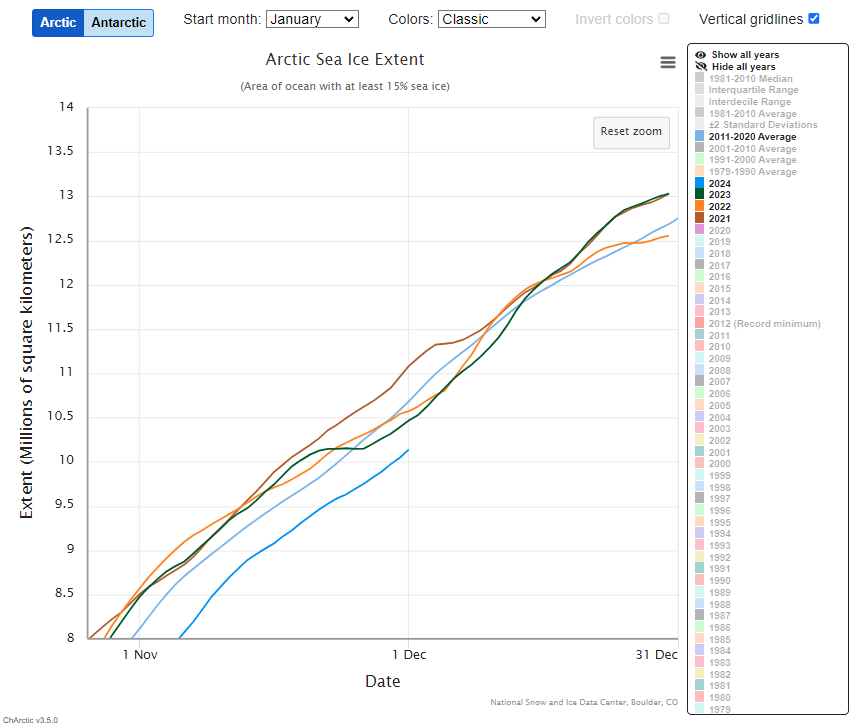

That it may be occurring (or beginning to occur) during the current decade was something I realised at the beginning of 2024 – and have been following closely all this year and intend to do so into 2025 (at least I hope I can). The upcoming end of 2024 will mark 40% of the ten year records for the decade and the four year averages so far recorded provide some hope of a slow-down or even a complete stop to the previous two decades of rapidly expanding loss of Arctic Sea Ice. There is even a glimmer of hope that a slight reversal to that trend may be occurring. The current 2024, it has to be said, after a good beginning – with the highest Winter ice formation in the decade so far – has not been helpful to the cause since August, but at the same time it has not actually broken the ongoing hopeful trend. The year appears to have a four year average of Sea Ice extent which is either well above or only slightly below the ten year average for the previous decade. And that is something quite remarkable in light of the recent history of the two previous decades.

As we enter 2025, the results of every month of that year will lay down the picture for 50% of future results for the decade. And there is no reason to think the second half of the decade would present anything different to the first half. Such is always a possibility of course, so until the beginning of 2031 – when all will have already been revealed – we can never be sure. But there is such a thing as the ‘balance of probabilities’ on which we can hang our hats. It is what we were given brains for.

I am not going to give any detailed results here as I have written extensively on the subject already this year. But I hope to keep reporting at least monthly as time moves on. And…

November has finished now, and has not been kind to this project. But it hasn’t derailed it. Throughout the month, November has wanted to play with the two previous ‘Leap Years’, 2020 and 2016 (a pure coincidence, I’m sure), as these were the two ‘baddest’ years of the previous decade (2012 – the fourth leap year) having been tamed by this stage and eager to comply with the best interests of mankind. But 2024 was never quite so ‘bad’ as those previous years. In fact, at the ‘1 Dec’ marker, the 4-year monthly average for Arctic Sea Ice was 10.564 million Km2, only a small amount below the 10 year average for the previous decade at 10.682 million Km2.

I should here acknowledge, with gratitude, the great work done by NSIDC (and NOAA who source the data) to produce the Arctic Sea Ice Extent Interactive Charts for our benefit.

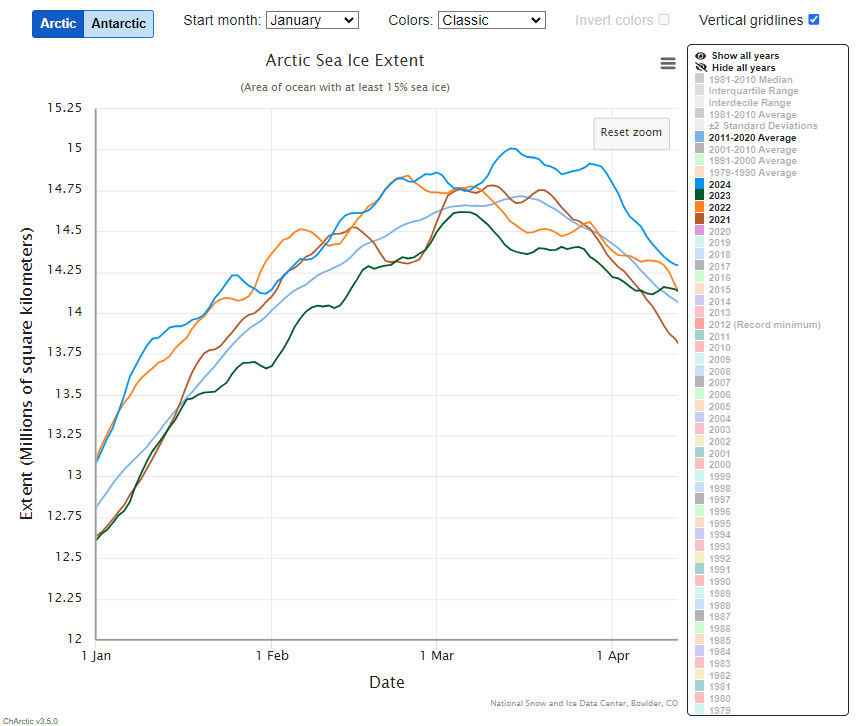

This year may end with 2024 remaining below the previous decade line, although stranger things have happened. But with two of the earlier years of the current decade well above that line and the third only a little below it, the year may end with a four year average in positive territory. A good start to the completion of the Winter ice-build season in the first quarter of next year. To the chart at right, showing that first quarter of the year, from ‘1 Jan’ will be added a new line with a different colour and starting at the end point of wherever 2024 happens to finish the year. That new line will be of great interest and importance as the year progresses, because it will mark the half-way point of the current decade at the date it is added, allowing us to gauge whether there is more or less ice on that date in the current decade than there was in the previous decade. That is an exciting prospect, and indicative as to whether the things I have been talking about are likely to be increasingly meaningful as the picture for 2025 continually builds. Each day or month could be another nail in the coffin for climate alarmism. The new year’s chart will initially look exactly like this year’s chart (for the months and years selected), since they have already been built – and recorded for posterity. Only the new line will gradually snake its way through, plotting its own course, as it happens.

It is quite exciting to know, or at least to suspect, that we are now witnessing, in real time, something never before seen or experienced by a technologically advantaged human population, while also knowing there is nothing we can do to prevent or hinder the process. Our adaptive genes may need to start functioning on a solution to survive it. Maybe that is what all those underground cities in Turkey were all about. Although, since nothing much I think was ever found in them, perhaps that is not the best idea to follow. Perhaps a migration to equatorial regions would be the best chance for survival of the species.

There may be errors of various types in (or more errors than usual). I don’t have time to check.

Leave a comment